Anxiety, worry, and panic are often used interchangeably. Although they are interrelated, they are different experiences. Understanding their distinct features is crucial for anyone who may be experiencing symptoms or knows someone who is.

In this blog post, we’ll explain what anxiety, panic, and worry are, when they become problematic, and treatment options. This article addresses the topic of “anticipatory anxiety” for those impacted. We’ll also address causes of anxiety disorders and how they’re diagnosed.

What are Anxiety, Worry, and Panic?

Anxiety and panic are normal responses to threat (Craske & Barlow, 2022; Zinbarg et al., 2006). They function as alarm systems to protect us. Anxiety, panic, and worry at manageable levels can help us when there is an objective threat. We want the alarm system to go off when there is actual danger because that means it’s working properly.

Anxiety

Anxiety occurs in response to anticipated threat (Craske & Barlow, 2022; Zinbarg et al., 1996). It activates our mind and body to prepare for future danger, so anxiety tends to gradually increase. For example, if you saw a tornado far in the distance while driving, it would be adaptive to drive to the closest shelter. Experiencing anxiety in that moment shows our mind and body are responding appropriately to an anticipated threat. Anxiety can be helpful to us at lower levels, such as improving focus and working towards a goal, and it doesn’t interfere with daily life. Thus, anxiety is not all bad.

Worry

One way anxiety prepares us for anticipated threat is by influencing our thoughts. Worry involves thoughts about bad things that may happen in the future and/or thoughts about our ability to cope with the worst-case scenario (Zinbarg et al., 2006). They often take the form of “What if…?” Worry can be about health, finances, work/school, relationships, and so forth. Worry is intended to help us keep potential threats in mind so we can problem-solve the situation. Understandably, worry increases with stressors and/or dangers. At manageable levels, worry is helpful to us as we are able to figure out a solution and move forward with it.

Panic

Panic occurs in response to immediate threat, activating the fight-flight-freeze response (Craske & Barlow, 2022). An example of panic would be if you saw a tornado nearby while driving. If you’re unable to make it to a safe shelter in that situation, then the next best options are getting as low as you can in your car and covering your head or getting out of your car and seeking shelter in a ditch or ravine. Experiencing panic in that moment helps us survive.

Anxiety and panic each have 3 components that influence each other (Craske & Barlow, 2022, Zinbarg et al., 2006).

Below is a table of them and some examples of each one:

| Anxiety | Panic | |

| When is the threat perceived to happen? | Future | Immediately |

| Physiological | Fatigue, muscle tension, trouble concentrating *Gradually increase | Heart racing, sweating, shortness of breath *Abruptly start |

| Cognitive | Thoughts about bad things that may happen and/or thoughts about our ability to cope with the worst-case scenario *Worrying to problem-solve | Thoughts related to fears of “going crazy, losing control, or dying” |

| Behavioral | Avoidance or safety behaviors (e.g. excessive reassurance seeking) | Avoidance or safety behaviors (e.g. avoid crowds or large places, only go in those places if someone is with you) |

These components can interact to heighten or decrease symptom intensity and level of distress. For instance, anxiety could start with noticing muscle tension (physiological), which may then lead to worrying (cognitive), followed by trouble concentrating (physiological). That could get in the way of completing tasks at home or work and further increase symptoms, creating a vicious cycle.

When do anxiety, panic, and worry become an issue?

Anxiety, panic, and worry become an issue when the alarm system doesn’t work as it’s supposed to – it doesn’t accurately distinguish between objective threat and perceived threat. That generates false alarms. False alarms can occur when 1) we perceive threat, though there is no objective threat, 2) our distress is out of proportion to the objective threat, 3) we avoid the situation that is not actually threatening, or 4) our avoidance of the situation is out of proportion to the actual threat (Craske & Barlow, 2022; Zinbarg et al., 2006). We experience the same physiological, cognitive, and behavioral responses with false alarms as with alarms for objective threats.

Anxiety is problematic when it is intense, excessive, persistent, and interferes with your day-to-day living (Craske & Barlow, 2022; Zinbarg et al., 2006). The anxiety may be challenging to manage, is out of proportion to the actual threat, and occurs for a long time.

Panic is problematic when there are repeated panic attacks, along with persistent concern or worry about future panic attacks or their consequences, such as having a heart attack, “going crazy”, or “losing control”), and/or significantly changing your behavior to avoid having another panic attack (avoid exercising, driving, being in large open areas, etc.) (APA, 2013). Here’s an example scenario of a panic attack: You’re walking in a crowded aisle at the grocery store. Suddenly, you notice your heart racing, you’re sweating and shaking, you feel short of breath and lightheaded, you feel flushed, and you’re afraid you’re losing control or having a heart attack. You feel extreme fear. You want to get out ASAP. You leave your cart in the aisle and run out of the store. In that example scenario, there was no objective threat. However, an immediate threat was perceived and panic symptoms onset abruptly.

Keep in mind that panic attacks aren’t specific to Panic Disorder (APA, 2013). They can occur in the context of other mental health conditions. For example, someone with Social Anxiety Disorder may have a panic attack before meeting someone new. Someone with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder may have a panic attack after encountering something that reminded them of past traumatic events they experienced.

Worry is problematic when it is excessive, persistent, difficult to control, and/or gets in the way of your daily life (Zinbarg et al., 2006). The worries cover multiple areas of a person’s life, including health, finances, work/school, relationship, etc. The worries typically focus on expecting the worst-case scenarios to occur, even when they are not likely. The worries may interfere with falling asleep and strain relationships. They may report “worrying about worrying” or experiencing “paralysis by analysis.” It may be difficult to make a decision about which option to go with and we may procrastinate on figuring out a solution and/or following through on it.

Thus, when anxiety, panic, and/or worry interferes with daily life, it’s time to seek professional help.

Prevalence of anxiety disorders

According to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (2024), anxiety disorders are the most common group of mental health conditions in the United States. It is estimated that 40 million adults (19.1% of the US population) has an anxiety disorder each year.

Recognizing signs of an anxiety disorder is a key step toward seeking help. If you’ve noticed these symptoms in yourself or someone you know, it’s essential to understand what anxiety disorders are like and to recognize that these are signs of a condition that may benefit from treatment.

What causes anxiety disorders?

Anxiety disorders are caused by a complex interaction among biological, psychological, and sociocultural risk factors (Craske & Barlow, 2022; Zinbarg et al., 2006). Biological risk factors can include genetics and brain chemistry and function. Psychological risk factors can include perception of threat, personality, and development. Sociocultural risk factors can include cultural/religious upbringing, cultural stigmas, and societal norms.

How are anxiety disorders diagnosed?

Diagnosis of an anxiety disorder typically involves a comprehensive assessment by a qualified mental health professional. They may combine information gathered from a clinical interview, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID; First et al., 2016), and self-report symptom questionnaires, such as the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (Liebowitz, 1987), Panic Disorder Severity Scale (Shear et al., 1997), and Penn State Worry Questionnaire (Meyer et al., 1990). The process often involves questions about anxiety symptoms, situations/activities in which the anxiety occurs, and how these symptoms affect daily life. Accurate diagnosis is key to receiving effective psychological treatment for anxiety disorders.

Treatment Options for Anxiety Disorders

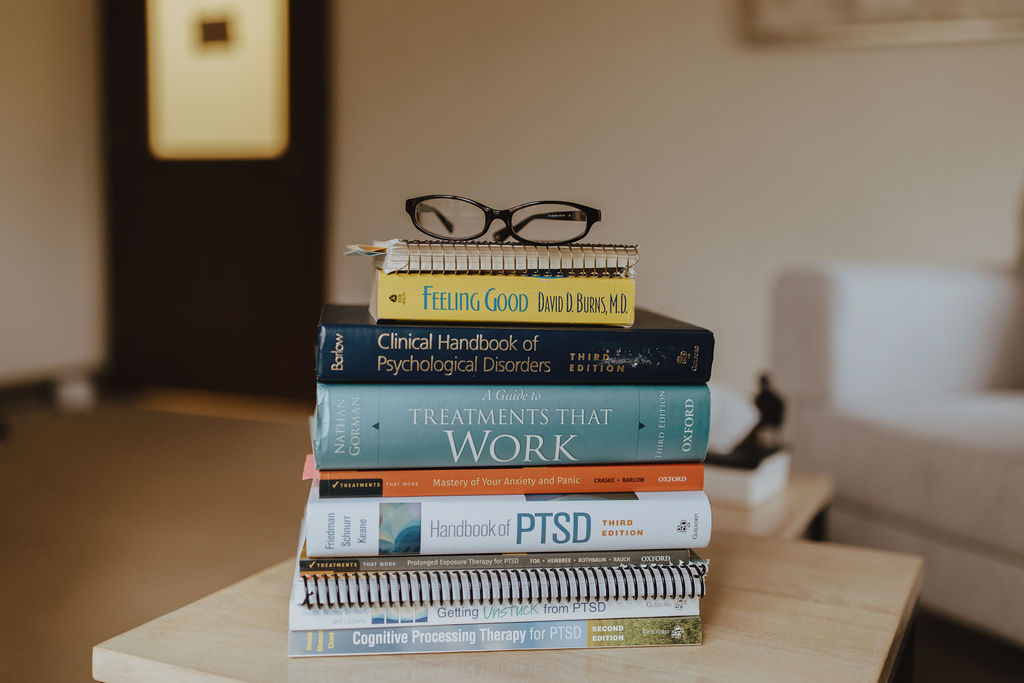

Are anxiety disorders treatable? Yes. There are several effective treatments available. Therapies for anxiety disorders vary in approach, and a qualified mental health provider can recommend the best course of action based on an individual’s symptoms and needs. Common psychological treatments include:

- Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT): Focuses on identifying unrealistic or unhelpful thoughts and developing more realistic and/or helpful thoughts.

- Exposure Therapy: Helps individuals gradually face their feared situation in safe environments. Facilitates learning that the feared situations are not dangerous and do not have to be avoided or the distress is out of proportion to the objective threat.

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): Focuses on changing the relationship to the thoughts. Also promotes acknowledging these experiences while engaging in actions that are important to us.

Each approach addresses psychological treatment for anxiety disorders in a unique way, providing options for people to find what works best for them.

Anxiety disorders affect millions of adults in the United States and negatively impact quality of life (Kavelaars, Ward, Mackie, Modi, Mohandas, 2023). Awareness, understanding, and appropriate assessment and treatment can make a significant difference. I provide effective, evidence-based psychological treatment for Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, and Social Anxiety Disorder in Ohio in person and via telehealth. Whether you’re seeking help for yourself or a loved one, understanding what anxiety, panic, and worry are is a step towards healing.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Anxiety and Depression Association of America. (2024, December 12). Anxiety disorders – facts & statistics. https://adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/facts-statistics

Craske, M.G., & Barlow, D.H. (2022). Mastery of your anxiety and panic: Therapist guide (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

First M.B., Williams J.B.W., Karg, R.S., & Spitzer, R.L. (2016). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV). Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association.

Kavelaars, R., Ward, H., Mackie, D.S., Modi, K.M., & Mohandas, A. (2023). The burden of anxiety among a nationally representative US adult population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 336, 81-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.04.069.

Liebowitz, Michael R. (1987). Liebowitz Social Phobia Scale. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry, 22, 143-171.

Meyer, T. J., Miller, M. L., Metzger, R. L., & Borkovec, T. D. (1990). Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behavior Research and Therapy, 28, 487-495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6.

Shear, M.K., Brown, T.A., Barlow, D.H., Money, R., Sholomskas, D.E., Woods, S.W., Gorman, J.M., & Papp, L.A. (1997). Multicenter collaborative Panic Disorder Severity Scale. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 1571-1575. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1571.

Zinbarg, R. E., Craske, M.G., & Barlow, D.H. (2006). Mastery of your anxiety and worry: Therapist Guide (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.